As Pakistan’s economy moves along its long-run trajectory, it has exhibited substantial changes in fundamentals that can be quantified mainly in terms of net economic growth gains and various other socioeconomic indicators.

By Dr. Eatzaz Ahmad

In today’s world where every citizen has at least some access to media, it is not surprising that there has emerged a flood of gossips on almost all important matters including economy in the name of news, information and transformation of knowledge. Information itself is an economic good which is now formally priced.

Unfortunately, most often negative news fetch relatively higher prices and gain more media space than positive news. For example, the news of increases in prices of consumer goods as ordinary as lemons or tomatoes that account for less than one percent of household budgets, occupy more prominent media space and time than the news of decrease in rents of dwellings that accounts for about 15 percent of the budget.

Against this backdrop, the present write up focuses on major achievements that Pakistan has made on economic front. Some weaknesses/failures are also noted with the aim to point out obstacles and weaknesses in economic planning and draw lessons for the future.

Besides somewhat satisfactory economic growth, Pakistan has also done well on a number of socioeconomic indicators.

On August 14, 2022, Pakistan celebrated its 75th birthday. During these 75 years Pakistan’s economy has experienced substantial economic transition along with a few episodes of major shocks (positive as well as negative). As the economy moved along its long-run trajectory, it exhibited substantial changes in economic fundamentals that can be quantified mainly in terms of real incomes growth, rise in debt liabilities, net gains of economic growth, and various other socioeconomic indicators like poverty (absolute as well as relative), human resource development, access to civic facilities, physical and social mobility, human rights, justice and environment. Like any other country, Pakistan’s performance during this period has been satisfactory in some but not all respects.

On macroeconomic front the most important indicator of performance is growth in income and per capita income. Income growth is important to evaluate a country’s capacity to meet the needs of a growing population and to build a viable economy in terms of its market size. On the other hand, if economic growth does not translate into rising per capita income, we can say that the growth has been insufficient. Let us, therefore discuss first the two important indicators, GDP and per capita GDP. The first two fiscal years since independence, 1947-48 and 1948-49 are skipped from the analysis as a period of transition for the newborn country when all efforts were directed towards settling the migrants.

The data reveal that Pakistan’s GDP at constant prices (meaning that the effect of price inflation is netted out) increased by about 30 times. At first, this number seems unbelievably too large. But if we take into account the factor that during this period Pakistan’s population grew by about 6.8 times, the number makes some sense. Discounting GDP growth by population growth indicates that per capita GDP of Pakistan increased by almost 4.4 times. For an easy understanding, we can say that per capita income has grown from Rs 5196 per month in the year 1949-50 to Rs 22781 per month in 2021-22 when both the numbers are measured at current prices (prevailing in the year 2021-22.). This is a reasonably good performance, though one may argue that many other countries, especially the neighboring countries like China, India and even Bangladesh grew faster than Pakistan. Despite an impressive start, Pakistan lost its growth momentum most probably because, as we shall note later, it failed to put similar effort towards institutions building.

Another commonly adopted argument to discredit Pakistan’s growth performance is that Pakistan achieved economic growth at the cost of huge burden of external debt (the so-called borrowed growth argument). To a certain extent it is true that past borrowing hunt back in the form of debt servicing (interest plus debt retirement) costs. A large share of government’s budget allocated to debt servicing and the expenditure on public administration being quite inelastic, the burden of debt servicing inevitably falls on development spending, which in turn adversely affects economic growth. A counter argument, however, is that the debt burden as a percentage of GDP (currently at 26%) is still within sustainable limits that can be justified against the welfare gains made possible through project aids, even though it often creates crisis like situations because of weak policy coordination, especially directed towards trade and industry.

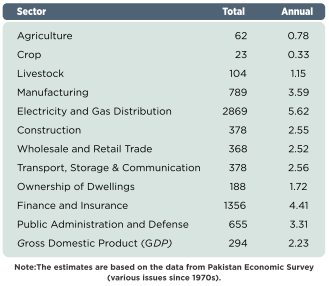

Moving now to other indicators of economic performance, we confine further analysis to the past 63 years, from 1959-60 to 2021-22 because reliable data for the previous years are difficult to find. Table 1 shows percentage growth in GDP of various important sectors of the economy. Some of the hallmarks of our growth experience include 3.6 percent annual growth in per capita manufacturing output or a total of 789 percent growth over the entire period of 63 years.

Per capita output of electricity and gas distribution has increased by phenomenal 5.6 percent during the same period, which far exceeds the overall per capita GDP growth rate of 2.2 percent. This obviously indicates that despite the fact that electricity price has increased many folds, both the household and production sectors have willingly increased electricity consumption at a much faster pace than the pace of overall economic growth.

The implied rising share of power consumption in household budget implies that living standards of households have improved as they are gradually adopting to the use of electric appliances and gadgets. Some of the other sectors that show impressive growth are finance and insurance, and public administration and defense.It appears that crop output per capita grew at a very slow pace. However, the overall growth performance of agricultural sector is somewhat rescued by a better growth in livestock output. Nevertheless, as frequently pointed out by experts and academic studies, agricultural sector of Pakistan remained unduly neglected to the extent that Pakistan can no more be regarded as an agriculture-based economy.

The fruit of economic growth has also reached to poor segments of society as the income shares of the 20% poorest population and 10% extremely poor population have slightly improved from 8.3% and 3.5% in 1949-50 to 9.6% to 4.2% respectively in 2018. Access to clean fuels and formal sanitation have also shown improvements.

Besides somewhat satisfactory economic growth, Pakistan has also done well on a number of socioeconomic indicators. Life expectancy at birth, which is not only an indicator of access to food and health facilities but also considered as a measure of poverty, has shown remarkable improvement from 45.3 years in 1960 to 67.4 years in 2020. This was made possible mainly because of better health facilities and, especially, successful immunization drives that reduced infant mortality rate significantly and improved health status of adult population considerably. This assertion is further supported by substantial improvements in the prevalence of stunting and undernourishment.

In contrast to success in the health sector, the success rate in the other human capital variable, namely education, has not been up to the mark. Although literacy and enrollment rates have increased and higher education sector has shown tremendous growth in the recent years, the emphasis has been on quantitative targets at the cost of quality. Since education, especially the higher education, has been partially provided by public sector and as a whole regulated by government, the poor performance in the sector reflects institutional weakness. One notable reflection of this weakness is that education policies tend to promote primary education with the aim of rising literacy rate or to focus on higher education to increase the number of PhD degree holders. This dichotomous approach that misses intermediate education has resulted in a higher number of PhD degree holders with weak foundations.

The performance of state institutions is important not only for the efficient and equitable provision of certain types of goods and services like national defense, infrastructure, education, health, sanitation and other civic facilities, but also for providing a conducive environment that enables private economic agents make efficient, productive and sustainable decisions. State institutions are also supposed to guarantee protection of civic and property rights of the existing and future generations.

Pakistan’s experience on the performance of state institutions has been quite disappointing. Table 2 shows that Pakistan has lost its position on most of the indicators of governance, specifically Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law, and Voice and Accountability.

Other such indicators like the performance ratings on human resource development, business regulations, fiscal policy, current account and debt policy, macroeconomic management, resource tapping, environmental sustainability, property rights, gender equity, social protection, transparency, accountability and corruption, also do not show any improvement in recent years.

Pakistan’s economy is significantly influenced by world’s political economy. But Pakistan has not played its cards well to benefit from its important strategic geopolitical position on the globe. Pakistan’s political alignment has often been in clash with its economic interests with the result that it could not benefit from trade with Iran, Russia and Central Asia, and it could not exploit full potential of long-term strategic economic coordination with China. Pakistan also suffered enormously in terms of terrorism and its offshoot in the form of internal conflicts because of its strategic alignment. This not only resulted in loss of tens of thousands of precious lives but also had adverse economic consequences in terms of losses in foreign investment, trade and tourism activities.

In a nutshell, Pakistan has achieved reasonably good progress on economic front resulting in substantial improvement in living standards despite the occurrence of adverse external shocks. However, since good state institutions play critical role in designing long-term strategic policies necessary for sustainable socioeconomic development, government of Pakistan has to divert its attention towards institution buildings and redirect its efforts from the role of provider to that of a facilitator.

The writer is an economist & Professor on State Bank of Pakistan Memorial Chair Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad